See details

READ MORE

Rehabilitation after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament

Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is accepted as the reference treatment for individuals with functional instability due to an ACL deficiency. The number of reconstructions is estimated to be around 60,000 - 75,000, although other authors speak of 350,000 reconstructions performed annually. Although 90% of reconstructions are performed by surgeons who perform less than 10 ligamentoplasty interventions per year, the success rate of this procedure is high, ranging from 75 to 90%. However, we must note the great failure potential of these primary reconstructions.

In evaluating a patient with persistent complaints following a primary ACL reconstruction, the first and most important step is to define the failure of the ACL reconstruction (RACL). Currently, there is a lack of consensus regarding the criteria that define the failure of ACL reconstructions, there is a low correlation between the patient's perception and the objective assessment of knee stability. Safran and Harner proposed a definition of RACL failure, attempting to combine both the patient's subjective perception and the objective clinical data collected by the surgeon. Failure was thus defined as "functional instability during daily activities or sports activities, the knee showing increased laxity on physical examination and instrumental testing." based on this definition.

Assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery in RACL failure are complex. The success of the RACL review requires a correct diagnosis in terms of the cause of failure, proper preoperative planning, proper patient selection, a well-executed surgical technique, and individualized recovery programs for each patient. Usually, the results of ACL revisions are inferior to primary reconstructions. Also, returning to the same level of performance before the injury is more difficult to achieve after the ACL revision. Despite these challenges, the results of ACL revisions can be favorable through attention to detail, meticulous pre-operative planning, and compliance with the principles of surgical technique and recovery.

The rehabilitation

Following the ACL review, the patient's ability to return to the same level of performance as before the ligament injury will largely depend on the recovery program. The ACL review is a challenge for both the surgeon and the physiotherapist. Recovery is different from case to case, being specific to each patient. Typically, recovery after the ACL overhaul will take longer. To date, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the content, timing and purpose of recovery after the revision of the ACL.To truly understand the principles underlying individual patient-specific recovery following ACL review, we need to understand the history and progress of primary RACL over time. From a historical perspective, the recovery of RACL changed considerably with the introduction of surgery in the early 1900s. Poor and unstable results during the twentieth century led to the emergence of standard protocols for both preoperative and postoperative surgery in primary reconstructions. In the 1970s and 1980s, many authors recommended conservative recovery through 6-8 weeks of immobilization, 8-12 weeks of crutch use, and many forbade returning to sports for at least 12 months postoperatively.

.jpg)

Recovery objectives in ACL revisions

Currently, the recovery objectives following the RACL review are similar to those of primary reconstruction, but at a slower pace, specific to each patient. Although the long-term goals of the LACL review are similar to those of the primary RLIA, many reports indicate that the return to the pre-injury pace is unrealistic. The basic principles of primary post-RACL recovery are well known in the literature. Recovery in primary RACL focuses on loading and range-of-motion exercises, obtaining a complete passive extension of the knee, complete recovery of neuro-muscular control, and using perturbation exercises to improve the result.Postoperative recovery in patients with ACL revision must be individualized to each patient and consider several factors. These factors relate primarily to the surgical technique and the selection of the type of graft, the patient's characteristics (age, body mass index, etc.), and the patient's expectations. The presence of concomitant lesions is another important aspect that will influence postoperative recovery. It has been shown that less than 10% of patients undergoing ACL review have morphologically normal articular cartilage or menisci at the time of the review. Therefore, the reconstruction of secondary stabilizers and articular cartilage are the most important factors that influence the need for an individualized program.

The recovery of these patients can be divided into 6 common general steps, focusing on key recovery goals. While aggressive recovery and early rehabilitation following consecutive primary RACLs are normal today, this principle is absolutely the wrong approach in RACL reviews. Multiple studies have shown that too aggressive recovery can result in early graft failure (in the first 6 months), as well as late ligament laxity (after the first 6 months). The patient with ACL revision will benefit from a slower and more cautious schedule for several reasons. First of all, allografts are used in RACL revisions, in which bone graft healing takes longer. Also, the sterilization process of allografts can cause the graft to be incorporated/fixed later. Consequently, To ensure a favorable biological fixation, a slower recovery program is recommended. In addition, RACL failure may have occurred as a result of an early return to current activities or as a result of incomplete neuromuscular control, so a more cautious approach may reduce the risk of further failure. Finally, the vast majority of patients with revisions have concomitant intra-articular injuries that are either treated surgically and require a longer recovery time or are not compatible with surgery and consequently require a slower recovery schedule. so a more cautious approach can reduce the risk of further failure. Finally, the vast majority of patients with revisions have concomitant intra-articular injuries that are either treated surgically and require a longer recovery time or are not compatible with surgery and consequently require a slower recovery schedule. so a more cautious approach can reduce the risk of further failure. Finally, the vast majority of patients with revisions have concomitant intra-articular lesions, which are either treated surgically and require a longer recovery time or are not compatible with surgery and consequently require a slower recovery schedule.

First stage: Initial postoperative stage (0-4 weeks)

The first stage of the recovery program focuses on minimizing muscle atrophy by modulating pain and reducing swelling, by neutral extension and early activation of the quadriceps. The initial stage generally lasts 2 to 4 weeks. A knee orthosis, fixed in full extension, is recommended. Exercises on the scale of the movements can be performed passively or actively, with help. The patient must first be accustomed to keep the knee in full extension, as opposed to the desire to support his knee on a soft pillow. Although the complete passive extension is an important consecutive aspect of primary RLIA, this aspect is not specifically pursued in the postoperative period of revisions, prioritizing neutral extension and graft protection. Effective swelling management during this initial stage will result in easier recovery of range of motion. Conversely, an aggressive approach in trying to regain full range of motion will cause pain and swelling, causing quadriceps muscle atrophy.The loading of the limb in the first 6-8 weeks will be delayed and will start with the loading of the fingers or not at all, in patients with special situations such as the repair of complex meniscus ruptures or with meniscus transplantation. The progression of the range of motion at this stage may be equally restricted at such an early time in the recovery program. Communication with the orthopedic surgeon is essential for the physiotherapist to ensure that progressive knee flexion is not harmful during this early recovery period.

.jpg)

Muscle activation exercises at this stage focus mainly on the quadriceps muscle, lifting movements of the limb in extension, and activating the muscles in the posterior thigh lodge. The ability to perform an efficient contraction of the quadriceps muscle, in full extension, is essential in gaining mobility of the patellofemoral joint and in preventing intra-patellar contraction. It was found that the existence of concomitant lesions will influence the recovery of neuromuscular control. For this reason, many authors recommend screening for anterior musculoskeletal lesions of the lumbar spine or lower extremities. For example, restrictions on movement in the ankle or hip will lead to improper loading of the knee. This recovery period is considered to be ideal for correcting these deficits, before moving on to exercises with a greater impact on the lower limbs. This can be achieved by lowering the lower limb, extension exercises of the hip with the knee joint at 90 degrees, and dorsiflexion and plantar flexion movements. The closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises in this recovery stage are based on the patient's loading limitations. If the operation did not require ligament, osteochondral, or associated meniscus procedures, then the loading process ranges from light loading of the fingers to full loading. CKC exercises will consist of rotational movements of the limb while wearing the orthosis,

Other additional exercises are ankle exercises and partial knee flexion.

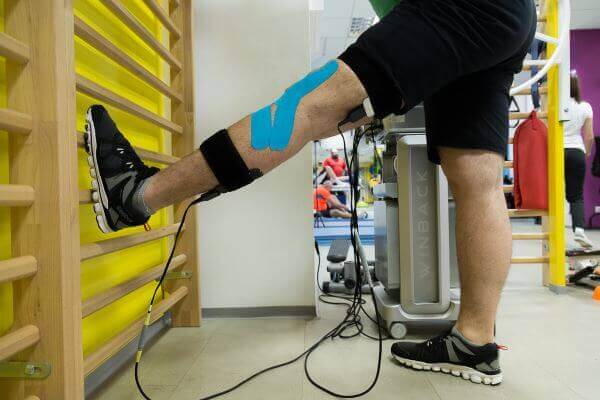

Cold local applications (ice) are effective in minimizing muscle atrophy but have not reduced the need for painkillers. Electrical neuromuscular stimulation is commonly used in early recovery periods to recover the quadriceps muscle and normalize its diameter.

No matter how well the patient feels during this recovery period, it is necessary to respect the loading status, the range of motion, and the limited movements, so as not to cause additional stress to the healing tissue. Considering the weakened neurophysiology of the knee, excessive stress applied to the healing tissue is not immediately manifested by pain or edema, but by late instability or persistent mechanical symptoms that may contribute to suboptimal results.

Second stage: Subacute postoperative stage (2-8 weeks)

During the second stage, which usually lasts 2 to 8 weeks, recovery progression is allowed if the pain is well controlled and the swelling of the knee has decreased over time. This period is marked by progressive loading, mobilization exercises, light cardiovascular exercises and neuromuscular control exercises. Except for loading limitations due to concomitant tissue damage or osteochondral repair procedures, full-load walking at 2 weeks will be promoted. Walking with the orthosis locked at 90 degrees will limit the non-sagittal stress caused on the knee joint and will protect the patient from forced knee flexion, in case the patient will suffer an uncontrolled knee flexion.Exercises that can help to regain the correct swing phase include walking on the spot with progressive knee flexion, and walking on the treadmill, performed with verbal feedback from the physiotherapist or with visual feedback by using mirrors. If the patient's gait is altered due to pain, light walking is recommended. One option to consider is hydrotherapy. Although walking in the pool is effective in reducing the patient's weight, the forces that reflect on the limb while moving through the water are not the same as the forces during normal walking, so the patient can gain an impaired gait.

The implementation of neuromuscular control exercises depends on the loading status. In patients who are not allowed to fully load at this stage of recovery, the neuromuscular control exercises are the same as in the first stage. If the patient can bear the full load, then he can perform a greater variety of exercises. These will include open kinetic chain exercises, closed kinetic chain exercises, the center of gravity strengthening exercises, and gait training exercises.

Closed kinetic chain exercises can be implemented once the soft tissue healing begins while looking at the quality of the patient's movements. The progression of a patient to closed kinetic chain exercises, with increased range of motion without considering the technique of their execution can cause compensatory movements that are difficult to correct. Closed kinetic chain exercises can include terminal extensions with Theraband resistance, incomplete knee flexions, tip lifts, dominant limb knee flexions, and leg press exercises (the range of motion of the knee will be 0-90 degrees). Also, ascent and descent exercises with a height of 5-10 cm can be introduced.

Open kinetic chain exercises, in addition to the exercises in Stage 1, may include the isometric extension of the knee with flexion of 90-60 degrees and active extensions from 90 to 45 degrees. Studies show that these exercises, performed with a limited range of motion from 90 to 35 degrees, do not cause tension harmful to the ACL graft. Extensions from 30 to 0 degrees, with a weight applied to the ankle, can, on the other hand, cause different degrees of tension on the ACL graft. Incorporating these exercises into the recovery program around the 6-week postoperative period was associated with better results compared to recovery that focused only on closed kinetic chain exercises.

Strengthening the center of gravity and stability play an important role in returning to high-level activities and reducing the risk of a new injury. At this stage, patients can perform lateral floats, frontal floats, and the bridge to the mattress. When the patient can complete the bridge, recovery progression may include one-leg support or one-leg bridge.

Low-intensity cardiovascular exercise is important at this subacute stage. Exercises can be initiated on the bike, emphasizing the quality of movements and the gradual progression of volume (time) and intensity (speed and endurance). While the bicycle can be used to regain knee flexion, it should be approached with caution, rather than approaching an aggressive strategy that leads to compensatory movements. Equally effective in this is the implementation of hydrotherapy. The buoyancy provided by the exercises in the pool can allow the improvement of the quality of the loaded exercises (walking training and neuromuscular exercises) and the advancement of the scope of the knee movements.

Stage 3: Initial neuromuscular stage (6-12 weeks)

Recovery in weeks 6-12 focuses mainly on strengthening exercises, improving the mobility of flexion movements (35 to 0 degrees), preparing for jogging, and early agility exercises. As a paradox, this period occurs at the same time as the ligament is at its weakest in terms of tensile strength and has a high risk of stretching. Due to this reason, as well as due to the need for additional precautions in RLIA revisions, many authors prefer a slightly different approach at this stage of recovery.Because most patients undergoing RLIA review undergo concomitant procedures or altered intra-articular tissue, impact exercises may be delayed until complete neuromuscular control (strength and endurance) develops. This small delay will also improve the homeostasis of the knee joint, which is supposed to be longer than one consecutive primary RLIA. The orthosis will be removed at the beginning of this stage, except in more severe cases (in which large ligament or osteochondral reconstructions have been performed). Knee movements in this phase should include neutral extension and flexion greater than 120 degrees at 12 weeks after surgery. The inability to acquire neutral extension will cause a pathological contraction pattern of the quadriceps (recruitment of the quadriceps coupled with knee flexion). If this contraction continues, the patient will develop quadriceps atrophy and previous knee pain due to high forces that affect the patellofemoral joint when the knee is in the flexed position. Passive recovery of terminal movements from complete knee flexion, with the help of a specialist, is not recommended. The delay in complete flexion is primarily due to residual swelling of the knee which frequently worsens with aggressive stretching movements. The swelling resolution corroborated with the patient's ability to perform the complete flexion movement.

Normal gait must be acquired at this stage. The exercises performed to accomplish this goal are represented by walking forward and sideways with the help of a special medical recovery ladder, cones, or with the help of small obstacles (6-8 ”). Walking training during this period may include side and back steps. Additional exercises must also include correctly performed ascent and descent exercises to implement appropriate mechanical movements. As long as the patient succeeds in performing correctly ascending and descending movements with a step of 10 cm, the height of the step can go up to 15-20 cm. Eccentric loading has been shown by Gerber et al to be an effective and safe means of strengthening the lower extremity following the RACL revision and can be implemented during this period. Performing eccentric squats, with a limited resistance/body weight, allows the patient to acquire the correct technique before increasing the intensity.

The balance exercises in one leg progress to their realization with the eyes closed or open, but accompanied by different head movements in various directions.

Cardiovascular training at this stage should include freestyle swimming, medium-difficulty cycling (intensity variation or a pre-set program), and ergometer exercises. If the patient has adequate neuromuscular control and no swelling, he or she may agree to begin elliptical exercises. During the initial attempt to perform these exercises, the physiotherapist should note the quality of the movements and the lack of swelling as an index of the patient's preparation for these new exercises. Subtle swelling of the joint usually manifests itself as low comfort, or a feeling of pressure, at the end of flexion or extension movements. The patient who has these symptoms will need a decrease in the volume and intensity of exercise.

Stage 4: intermediate neuromuscular control (12-20 weeks)

At this stage, exercises for neuromuscular control will progress, taking into account the healing of soft tissue and homeostasis of the knee joint (pain and swelling). The ACL graft will acquire resistance as well as load tolerance; however, the graft remains prone to stretching due to too aggressive recovery. While primary RACL recovery progresses to impact exercises such as jogging and agility training, a more conservative approach is preferred in RACL revisions.Regardless of the concomitant procedures, this stage must also include the symmetrical flexion of the knee. Normal gait should be present at the beginning of this stage. A complete analysis should also include walking feedback while climbing and descending stairs. Walking training exercises include walking with the knees raised, walking with obstacles, and sidestepping. Resistance walking (performed by an elastic band placed around the patient's torso or lower extremity) can also improve neuromuscular control.

The strengthening exercises in this stage will further incorporate OKC and CKC exercises. Knee extensions will be performed with a 90-45 degree limitation of movements to minimize the stress of the anterior tibial translation on the healing of the ACL graft. During this stage, the focus is on CKC exercises. During CKC exercises, patient care should focus on avoiding dynamic valgus and on quality, not quantity, gait. To implement this approach, the author recommends 3 to 5 sets of each exercise lasting at least 20 seconds.

The progression of the exercises can be obtained by manipulating several variables of the exercises. These may include increasing exercise time (from 20-30 seconds to exercise exceeding 45 seconds), improving joint mobility, increasing movement speed, incorporating multiple movements for the same exercise, and adding varying degrees of resistance (eg use of a medicine ball or dumbbells).

Squats of the dominant hip continue to be accentuated at this stage and progress to the use of dumbbells or other weights. Multiple-acting cramps are recommended for increased neuromuscular demands. While forward flexions are the most common, adding lateral, anterolateral, or posterolateral flexions is an effective way to develop movement awareness and neuromuscular control, thus preparing the limb for greater functional requirements. Towards the end of this stage, if there is no minimal swelling or pain, patients can begin training with jumps, thus preparing for the next stage of the recovery program.

External resistance, using dumbbells, medicine balls, or resistance bands serves as additional stimuli in regaining neuromuscular control. Increased resistance during squats does not cause additional stress on the ACL compared to weightless squats. The exercises begin with the patient holding the weights at the hip (the arms being extended along the side of the hip) and advancing to support the weights at the shoulder during the CKC exercises. Traditional squats, with the dumbbell along the back, are not recommended at this stage because they can frequently cause movement alterations and additional stress on the healing graft. To potentiate the neuromuscular requirement,

Progress in the center of gravity strengthening exercises may include torso movements, running with the knees to the chest, push-ups or knee flexions with the arms above the head or previously positioned, and push-ups with 3 support points. These exercises will create additional demands for the stability of the center while performing coordinated movements of the extremities. Continuation of swimming, elliptical or medicinal cycling, and stair climbing exercises are the main means of conditioning at this stage. To vary the training stimulus, frequent changes will be made in the selection of exercises and/or the change of the pre-set program for the exercise machines.

Stage 5: late neuromuscular control (20-32 weeks)

This late stage of the recovery program is characterized by the beginning of training with more complex exercises, which will mimic the patient's occupational demands, recreational needs, or those of competitive sports. Until this stage, the rotational forces that reflect on the knee have been avoided, since these exercises can cause dynamic valgus stress on the knee. In patients with extensive meniscus repair, meniscus allograft, or major articular cartilage repair, we will delay the introduction and progression of these exercises by up to 24 weeks.Although the range of motion of the knees should be almost symmetrical at this time of recovery, it is imperative to continue the gentle stretching to obtain the final flexion movement. As mentioned in the early stages of recovery, it is also important to ensure a good range of motion in the adjacent joints (talocrural and hip joint) as well as in the lumbar spine. Limitations of movement in these areas will contribute to subtle but potentially cumulative stress on the knee joint.

Neuromuscular control at this late stage will include more resistance and volume for previous exercises. The exercises performed vary and include push-ups with concomitant movements of the torso or upper limb (trunk rotations or the approach of the arms above the torso), partial squats with the press, and climbing stairs with weights. Open kinetic chain exercises will be performed further for isolated muscle strengthening. Closed kinetic chain exercises will also include anteromedial flexions. These exercises will produce valgus forces on the knee, so the physiotherapist must ensure that the patient understands this risk and is willing to avoid it.

The strengthening of the center of gravity and the lower extremity will continue at this stage. The changes that occur include a wider range of one-leg support exercises and changes in the support surface. An example is standing in one leg and training the upper body (press above the head or rotations of the torso). Also, disturbance exercises can be incorporated in this stage. Ways of performing include the use of resistance bands, support on an unstable surface, and the modification of visual or vestibular information. The resistance band will also include imposing valgus stress on the lower extremity by applying a resistance band above or below the knee joint during squats or around the torso during gait training activities (walking forward / ascending). on a high step or the lateral ascent of the steps). Visual and vestibular changes include one-legged balance exercises with the eyes open or closed or the incorporation of rotational, diagonal, or vertical movements of the head and neck during squats.

In patients with concomitant injuries (meniscus repair, meniscus transplant, or osteochondral repair), jogging will be initiated in the pool. Full load jogging will not start until 24-28 weeks. The emphasis is on the symmetrical gait model because studies have shown that an asymmetry while walking persists for up to 1 year after the RACL revision. Towards the end of this stage, running exercises with a change of direction must be implemented (jogging in the form of the number 8 or turning 45/90 degrees).

Stage 6: Return to activity without restrictions (32-54 weeks)

The final stage of recovery is marked by the analysis of the needs of the sport practiced or occupational that are necessary for the patient to return to the desired level of activity. Although many guidelines have been stated on returning to sports, there are still questions about returning to safety that does not involve long-term ramifications through activities with high needs on the knee joint. Studies show that asymmetrical movements during cramping or jumping persist even more than a year after ligament reconstruction. Therefore, the emphasis is on the quality of movement and the acquisition of a satisfactory neuromuscular control, which allows returning to sports in complete safety. Functional tests are recommended at the beginning of this final stage to provide data on areas of deficiency. Examples of functional tests include one-legged jumps, vertical jumps, and agility tests. Isokinetic tests can also assess the symmetry of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles in terms of strength and endurance symmetry. Neuromuscular control exercises include dumbbell straightening, depending on the patient's occupational / sports demands. Jumping training can progress at this stage and includes "box jumps" with progressive degrees of difficulty and changing direction during jumps.

Pre-planned movements should be replaced with reaction movements because studies have shown that neuromuscular activity and the associated stress on the lower extremity joints change when performing these reaction tests. Consequently, to maximize the availability of returning to sports at the same level of performance and to reduce the risk of a new injury, these reaction tests must be implemented. Reaction tests may include changes in direction during jogging/running.

The final return to running activities at this stage must analyze the needs of each patient and take into account the psychological preparation to return to the same level of performance, before the ligament injury. The area of the field on which the patient will run must be taken into account and the need to include the sprint, quick lateral movements (as is the case in basketball), or back running.

Conclusions

The revision of the ACL should be seen as a "rescue" intervention, the recovery program being more conservative compared to that of the primary reconstructions. The recovery program following the revision is influenced by a large number of variables, which take into account both the surgical technique used and the needs of the patient. Thus, we will not use an accelerated program, but an individualized one for each patient, slower and more cautious, which respects all the variables, to ensure a satisfactory surgical result.

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT

CONTACT US

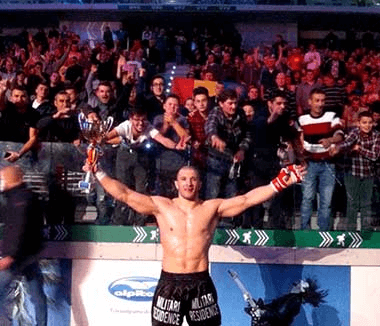

SUCCESSFUL RECOVERY STORIES

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT

FOR AN EXAMINATION

See here how you can make an appointment and the location of our clinics.

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT